Introduction to Aging and IQ

As we journey through life, the way our brain functions evolves in complex and fascinating ways. Understanding aging and IQ involves exploring how different cognitive abilities change over time, particularly processing speed and crystallized knowledge. These components of intelligence do not decline uniformly; some aspects improve or remain stable, while others may diminish due to natural aging processes.

The study of cognitive aging is crucial for recognizing how brain health impacts intellectual performance. This article delves into the nuanced relationship between aging and IQ, highlighting the mechanisms behind changes in cognitive function and offering insights into maintaining mental acuity. Whether you are curious about how your IQ might shift with age or interested in strategies to support brain health, this comprehensive guide covers key concepts with depth and clarity.

Key Insight: Aging affects different types of intelligence in unique ways—while some mental faculties slow down, others can remain robust or even improve, reflecting the brain's dynamic nature.

Understanding the Components of IQ and Their Relation to Aging

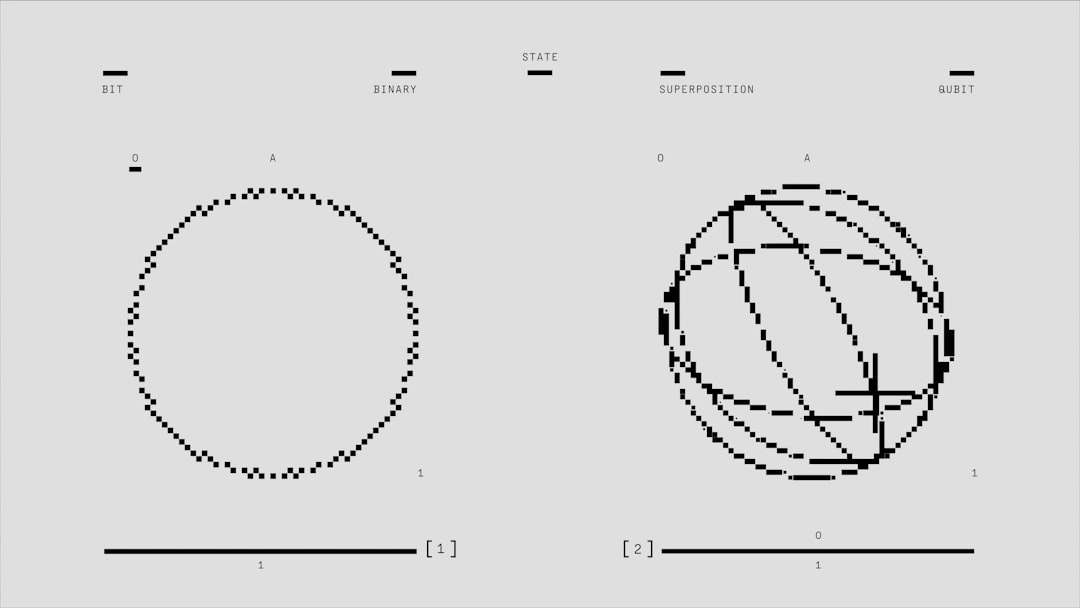

To grasp how IQ changes with age, it is essential first to understand the two primary components of intelligence: fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. Fluid intelligence refers to the ability to solve new problems, reason abstractly, and process information quickly. It is closely tied to processing speed and working memory. In contrast, crystallized intelligence encompasses accumulated knowledge, vocabulary, and skills gained through experience and education.

Research indicates that fluid intelligence tends to decline gradually starting in early adulthood, primarily due to slower processing speed and reduced working memory capacity. Conversely, crystallized intelligence often remains stable or even improves with age, as lifelong learning and experience enrich this domain. This divergence explains why older adults might find novel problem-solving more challenging but excel in tasks requiring accumulated knowledge.

For example, an older adult might take longer to complete a timed reasoning task but perform exceptionally well on vocabulary or general knowledge questions. This pattern underscores the importance of distinguishing between different facets of IQ when considering cognitive aging.

The intelligence quotient is not a monolithic measure but a composite of multiple cognitive abilities, each affected differently by aging.

Understanding these differences helps in interpreting IQ test results across the lifespan and tailoring cognitive interventions appropriately.

Processing Speed Decline: The Core of Cognitive Aging

One of the most pronounced changes in cognitive aging is the decline in processing speed. This refers to how quickly the brain can perceive, interpret, and respond to information. Slower processing speed affects many cognitive tasks, including attention, memory encoding, and problem-solving.

Neurological studies suggest that age-related changes in white matter integrity and neural connectivity contribute to this slowdown. These biological shifts reduce the efficiency of neural transmission, leading to longer reaction times and decreased multitasking ability. For instance, older adults may find it harder to keep up with rapid conversations or complex instructions.

This decline has practical implications: it can affect everyday activities such as driving, decision-making, and learning new skills. However, it is important to note that processing speed decline is not synonymous with overall intelligence loss. Many older adults compensate by relying more on experience and knowledge, which are less affected by speed.

Key Takeaway: While processing speed slows with age, it does not necessarily diminish the quality of reasoning or judgment when given sufficient time.

Strategies to mitigate processing speed decline include engaging in mentally stimulating activities, physical exercise, and maintaining cardiovascular health, all of which support brain vitality.

Crystallized Knowledge: The Stability and Growth of Wisdom

Unlike processing speed, crystallized knowledge often remains stable or improves as people age. This form of intelligence reflects the wealth of information, vocabulary, and skills accumulated through education and life experiences.

Older adults frequently demonstrate superior performance on tasks involving language, general knowledge, and expertise in specific domains. This growth is attributed to continuous learning and the brain's ability to retain semantic memory over time. For example, a seasoned professional may outperform younger colleagues in problem-solving scenarios that draw on years of experience.

This phenomenon highlights the adaptive nature of intelligence: while some cognitive processes slow down, others become more refined. It also challenges the misconception that aging inevitably leads to cognitive decline across all areas.

Practical Application: Leveraging crystallized knowledge can compensate for slower processing speed, enabling effective decision-making and problem-solving even in later years.

Engaging in lifelong learning, reading, and social interactions can help maintain and expand this valuable cognitive reserve.

Brain Health and Its Impact on IQ Changes with Age

Brain health is a pivotal factor influencing how IQ changes with age. Maintaining a healthy brain involves a combination of lifestyle, genetics, and environmental factors that affect cognitive resilience.

Physical exercise, balanced nutrition, stress management, and adequate sleep contribute significantly to preserving brain function. For example, aerobic exercise promotes neurogenesis and improves blood flow, which supports cognitive processes including memory and attention. Conversely, chronic stress and poor diet can accelerate cognitive decline by increasing inflammation and oxidative stress.

Moreover, engaging in cognitive training and mental challenges has been shown to enhance neural plasticity, potentially slowing age-related IQ changes. Using our practice test and timed test can serve as valuable tools to stimulate the brain and monitor cognitive performance over time.

The American Psychological Association emphasizes that brain health is a modifiable factor that can influence cognitive aging trajectories.

Understanding these influences empowers individuals to take proactive steps toward sustaining their intellectual abilities throughout life.

Measuring IQ Across the Lifespan: Challenges and Considerations

Assessing IQ in the context of aging presents unique challenges. Traditional IQ tests often emphasize speeded tasks, which may unfairly disadvantage older adults due to natural processing speed decline. Therefore, interpreting IQ scores requires consideration of age-related cognitive changes.

Modern assessments distinguish between fluid and crystallized intelligence, providing a more nuanced picture of cognitive abilities. For instance, a comprehensive IQ test that includes verbal comprehension and reasoning tasks alongside timed problem-solving can better capture an individual's intellectual profile.

You can take our full IQ test or start with a quick IQ assessment to understand your cognitive strengths and weaknesses. These tests can help identify areas where aging may have impacted performance and areas where knowledge remains strong.

Important Note: IQ scores are relative measures and can fluctuate with health, education, and practice, especially as one ages.

Regular cognitive assessments can track changes over time, informing strategies to maintain or improve brain function.

Practical Strategies to Support Cognitive Aging and Brain Health

Maintaining cognitive health and mitigating IQ changes with age involves a multifaceted approach. Here are key strategies supported by research:

- Engage in regular physical activity: Aerobic and strength exercises improve cerebral blood flow and neuroplasticity.

- Pursue lifelong learning: Challenging the brain with new information and skills bolsters crystallized intelligence.

- Practice cognitive exercises: Using tools like our practice test and timed test can enhance processing speed and working memory.

- Maintain social connections: Social engagement supports emotional well-being and cognitive stimulation.

- Adopt a balanced diet: Nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants protect brain cells.

- Manage stress effectively: Chronic stress impairs memory and executive function.

Implementing these habits can slow cognitive decline, enhance brain health, and preserve intellectual abilities well into older age.

Blockquote: "The most critical factor in healthy cognitive aging is consistent engagement with mentally and physically stimulating activities."

Conclusion: Embracing the Complexity of Aging and IQ

The relationship between aging and IQ is intricate, reflecting the interplay of declining processing speed, stable or improving crystallized knowledge, and overall brain health. Recognizing that intelligence is multifaceted allows for a more compassionate and accurate understanding of cognitive aging.

By appreciating how different cognitive domains evolve, individuals can adopt effective strategies to maintain mental sharpness. Whether through physical exercise, lifelong learning, or cognitive training, there are actionable steps to support brain health.

If you want to explore your cognitive abilities further, consider taking our full IQ test or trying a quick assessment to benchmark your current performance. Regular evaluation paired with healthy lifestyle choices offers a promising path to sustaining intellectual vitality throughout life.

For deeper insights into cognitive psychology and intelligence, the Encyclopedia Britannica and the Wikipedia article on cognitive ability provide excellent resources.

Final Thought: Aging is not a uniform decline but a dynamic process where knowledge and experience can shine even as some cognitive speeds slow. Embrace this complexity to foster lifelong intellectual growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does processing speed specifically affect daily tasks in older adults?

Processing speed decline can make tasks that require quick thinking or rapid responses more challenging for older adults. Activities such as driving, following fast-paced conversations, or multitasking may become more difficult. However, older adults often compensate by relying on experience and taking more time to process information, which helps maintain functional independence.

Can engaging in cognitive training reverse age-related IQ decline?

While cognitive training cannot fully reverse age-related declines, it can improve specific cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and processing speed. Regular mental exercises, including using practice IQ tests or timed challenges, promote neural plasticity and may slow the progression of cognitive aging, enhancing overall brain health.

Why do some IQ tests disadvantage older adults more than others?

Many IQ tests emphasize timed tasks that measure processing speed, which naturally declines with age. Tests that rely heavily on speeded problem-solving may underestimate older adults' true cognitive abilities. Balanced assessments that include verbal knowledge and reasoning provide a fairer evaluation of intelligence across different age groups.

How important is lifestyle in influencing IQ changes with aging?

Lifestyle factors such as physical activity, diet, social engagement, and stress management play a crucial role in cognitive aging. Healthy habits support brain structure and function, potentially mitigating declines in processing speed and memory. Conversely, poor lifestyle choices can accelerate cognitive deterioration, highlighting the importance of proactive brain health management.

Are IQ scores stable throughout adulthood, or do they fluctuate with age?

IQ scores can fluctuate due to factors like health, education, and cognitive engagement. While crystallized intelligence tends to remain stable or improve, fluid intelligence and processing speed may decline, causing variations in overall IQ scores. Regular cognitive assessments can help track these changes and guide interventions.

What role does crystallized intelligence play in professional success for older adults?

Crystallized intelligence, which includes accumulated knowledge and expertise, often enhances professional performance in older adults. It allows them to draw on experience and apply learned skills effectively, compensating for slower processing speed. This form of intelligence is critical for decision-making, problem-solving, and mentoring roles.

Curious about your IQ?

You can take a free online IQ test and get instant results.

Take IQ Test